Occupy Central

Occupy Central is a civil disobedience movement which began in Hong Kong on September 28, 2014. It calls on thousands of protesters to block roads and paralyse Hong Kong's financial district if the Beijing and Hong Kong governments do not agree to implement universal suffrage for the chief executive election in 2017 and the Legislative Council elections in 2020 according to "international standards." The movement was initiated by Benny Tai Yiu-ting (戴耀廷), an associate professor of law at the University of Hong Kong, in January 2013.

OCCUPY CENTRAL - DAY 55: Full coverage of the day’s events

PUBLISHED : Thursday, 20 November, 2014, 5:13pm

UPDATED : Friday, 21 November, 2014, 5:10am

End occupation of Hong Kong and focus on mass electoral campaign for democracy

Albert Cheng says change in strategy needed to win back public sentiment and counter Leung's war of attrition, to avoid a political disaster at the polls

I am an old-timer. The umbrella movement is billed as an intergenerational conflict. What I have to say may not be music to young ears. Yet, like most grandparents, I will keep mumbling, screaming and doing whatever it takes to talk some sense into the heads of the student activists.

Those who are supposed to be leading the movement have formed a five-party platform to discuss their next moves. They include the pan-democrats, Occupy Central with Love and Peace, the Federation of Students, Scholarism and other civic bodies. My hopes are pinned on the student bodies.

The organisers have so far failed to come up with a clear strategy, let alone an action plan. The longer this goes on, the less popular the movement will become. The government will emerge as the winner from this gradual change in public sentiment. The campaign is in danger of dissipating into a public nuisance.

This trend has been confirmed independently by various surveys. An overwhelming 83 per cent in one poll said they wanted Occupy to end immediately. The under 30s are the only sector who tend to think otherwise. Slightly over half this age bracket want the sites in Admiralty, Causeway Bay and Mong Kok to remain occupied. For them, the movement will be a failure, until and unless the government makes substantial concessions over electoral reform. They prefer a forced eviction to a voluntary withdrawal.

The five-party platform has been toying with the idea of asking some directly elected legislators to resign so they can promote their ideas in all 18 districts during by-elections that would be called within six months. Such a pseudo-referendum could provide a turning point for the campaign. The pan-democratic camp could then use the electoral campaign to regain the momentum and refocus on the major stumbling block for true democracy in Hong Kong - Chief Executive Leung Chun-ying.

The student groups should call a mass assembly and announce a tactical withdrawal from the occupied sites so the protests can transform into a mass campaign across the districts. The window of opportunity is narrow, with major occupied areas due to be cleared within days.

Professor Chan Kin-man, one of the trio behind the original concept of Occupy, is apparently sensitive to the turning tide. He has in effect withdrawn from Admiralty and resumed his teaching duties on campus. He has written in support of the pseudo-referendum. He said the least the protesters should do is make the occupied sites smaller in return for greater support from the wider public.

However, the pan-democratic legislators' response has been less than warm. Those who gave up their seats would be barred from running in the by-elections under current electoral laws. They are dragging their feet out of self-interest. The students should apply maximum moral pressure on them.

Meanwhile, the pro-establishment camp has lost no time in maximising its political gains. Their blue ribbon campaign in support of the police is, in effect, a grand election campaign that has started early.

They are targeting citizens who used to be apolitical. The recent anti-Occupy petition, headed by Robert Chow Yung, claimed to have secured 1.8 million signatures. That may be inflated but even half that figure would be equivalent to the total number of votes the pan-democrats got in the geographical constituencies in the 2012 Legislative Council poll. In that ballot, support for the pan-democrats dropped from 60 to 55 per cent. It looks poised to slip further in the next election.

The one-third of citizens who are in favour of Occupy in principle are likely to vote for younger and more progressive candidates in the next district council and Legco elections.

The political awakening of the younger generation is by far the biggest achievement of the movement. The young activists should make the most of any by-elections to reach out to their peers and broaden their ballot bases. But the student leaders have lost sight of the reality that Leung is fighting a war of attrition and division. The attempt by a small group of radicals to storm the Legco building shows that the government tactics are paying off. Even Leung's approval rating has inched back above the 40-point threshold.

The young occupiers are chasing a democratic ideal, for which they should be given credit. Yet, all democratic systems boil down to a contest for votes. This movement for a fair and just electoral system is not backed up by tactical considerations to consolidate and enlarge the support of the general electorate.

The biting reality is that even as youngsters seek the holy grail of true democracy, their allies can barely hang on to their elected seats. Their democratic dream might turn into a political nightmare before too long.

Albert Cheng King-hon is a political commentator.taipan@albertcheng.hk

This article appeared in the South China Morning Post print edition as End Occupy movement and focus on by-election campaign to regain support

Half of Occupy Central protesters ready to pack it in if asked by organisers

Survey shows a near-even split between those who would go home if asked by organisers, and those who want to stay until demands are met

PUBLISHED : Thursday, 20 November, 2014, 11:36pm

Legal representatives place a notice on a Mong Kok barricade set up by pro-democracy protesters, to be removed by bailiffs under a court injunction. Photo: Sam Tsang

Half of Occupy protesters said they would retreat if asked to do so by campaign leaders, according to a poll of more than 2,100 people taking part in the sit-ins.

The findings, compiled by students and analysed by the Post, came as tycoon Jimmy Lai Chee-ying urged protesters to consider retreating.

Out of 2,183 protesters polled, 958 said they would retreat if the three groups leading the movement asked them to do so. The results also showed that 963 said they would ignore such a request and continue their protest, while 262 did not give a clear answer or were undecided.

The study was conducted by 20 student protesters and volunteers. Close to 2,000 protesters in Admiralty and about 200 in Mong Kok replied to questionnaires between Friday and Sunday.

Supporters of a retreat said now was the time to change their strategy to reach out to the wider public. Some said public support for the street protests, now in their eighth week, had been dwindling and staying would not give them a better chance of achieving their goals.

Those who vowed to stay said retreating would amount to an admission of failure, as the Hong Kong and central governments had not made any concessions on electoral reform proposals.

The study came as a University of Hong Kong poll conducted this week found nearly 83 per cent of Hongkongers wanted the protests to stop.

Occupy co-founder Dr Chan Kin-man said yesterday: "If half of the protesters would leave [if asked by organisers], the other half might actually rethink whether they should stay."

Chan, who has hinted several times that the sit-in should end, said organisers should now consider other strategies.

"Many people in the crowd are waiting for the student leaders to make the next move, and also for a way out," he said.

He said what the students had achieved was already beyond imagination, and that they should not have any "sense of failure" in calling for a retreat.

Media mogul Jimmy Lai, who has been camping in Admiralty, agreed that it was time for protesters to consider leaving to save energy for the long-term fight for greater democracy.

"Scholarism, HKFS [Federation of Students] or the Occupy leaders should give the government a deadline on when to respond. If the government doesn't act, then we'll come back."

Lai said some protesters wanted to get something from the government before they left, but this was not likely to happen.

"If you wait for that, or wait for action from Legco, are you really going to wait for a year?"

Another Occupy co-organiser, Benny Tai Yiu-ting, said he and the two other founders had postponed their plan to turn themselves in to police today, as they wanted to observe the clearance of protest areas in Mong Kok, expected next week.

Student leader Lester Shum said they were planning to stay at the occupied area in Mong Kok next week in order to get arrested as the operation took place.

This article appeared in the South China Morning Post print edition as Half of occupiers ready to pack it in

Four more arrested over Legco storming, including publication editor, Civic Passion members

Those nabbed in the action meant to further Occupy Central’s cause include a publication’s chief editor and radical Civic Passion members

PUBLISHED : Friday, 21 November, 2014, 3:10am

One of the glass doors at the Legislative Council complex that was smashed by masked intruders. Photo: Felix Wong

Police have nabbed another four men - including two from a radical political group and the chief editor of a free publication - over Wednesday's storming of the Legislative Council building.

The latest four arrested yesterday - bringing the total to 10 - include two Civic Passion members and Local Press chief editor Leung Kam-cheung.

They were held on suspicion of criminal damage, unlawful assembly, and accessing a computer with criminal or dishonest intent, police said.

Last night, police said the six men arrested on Wednesday would appear in Eastern Court today. Four are on holding charges of criminal damage and the other two are being charged with assaulting a police officer.

The news came as protesters who took part in the storming expressed disappointment at pan-democratic lawmakers who condemned their act, and warned that they might target other public buildings next.

Two protesters, a man and a woman who refused to give their full names, dismissed suggestions that they had been "misled" into storming the Legco building.

They knew exactly what they were doing and believed their action would further the Occupy Central pro-democracy movement's cause, they said.

At about 1am on Wednesday, a group of masked men, using bricks and metal railings, smashed two glass doors at the Legco building.

Hundreds of Occupy protesters flocked to the scene shortly after in a show of support for the masked men.

The ensuing chaos prompted police to charge at them with batons and pepper spray.

Later that day, three Occupy co-founders and 23 pan-democratic lawmakers "strongly condemned" their actions. Three radical pan-democrats, including "Long Hair" Leung Kwok-hung, urged the action's organisers to explain their motives.

The Occupy movement said some protesters had falsely claimed lawmakers would on Wednesday discuss a bill with implications for online freedom of expression. The bill will be discussed only next month.

But the woman protester said she had not been misled. She had gone to Admiralty on Tuesday night after seeing a post in an online forum implying that the forum users would be "doing something", she said.

"Do the pan-democrats think democracy will just fall from the sky?" she said. "We sat there for days but the government has not [made any concrete response]."

While she did not take part in smashing the doors, the woman said, she supported the action by tweeting from the scene.

"We were trying to increase the 'cost of governance' … And although we were unsuccessful, we caused some trouble for the police," she said, adding that she believed the streets of Central and other public buildings might be the protesters' next targets.

Her fellow protester said: "It's contradictory for the pan-democrats to slam us for staining the movement with illegal action, as blocking roads is also illegal."

Civic Passion leader Wong Yeung-tat said: "The timing was unwise strategically, but … I understand their anxiety that the movement has yet to bear fruit."

Meanwhile, Next Media founder and Occupy supporter Jimmy Lai Chee-ying said the protesters were just destructive.

"Obviously someone was creating false information to spark people off ... The objective was to paint this movement in a bad light," he said.

This article appeared in the South China Morning Post print edition as Four more men arrested over Legco storming

Top court judge defends integrity of Hong Kong's rule of law

PUBLISHED : Friday, 21 November, 2014, 3:10am

The rule of law in Hong Kong will survive no matter how severely critics of the courts say it has been undermined, a founding judge of the Court of Final Appeal said yesterday.

Mr Justice Kemal Bokhary rejected suggestions that High Court injunctions against the Occupy protesters had harmed the court's independence by involving it in a political issue, because the court "does not choose cases, but the cases are brought before the court".

But he declined to comment on whether the government was undermining the rule of law by relying on the court instead of police to solve the political stand-off between the administration and pro-democracy protesters.

"The rule of law, even if it takes a number of hits, will survive, because we … as people make it survive," Bokhary said.

Bokhary, a non-permanent judge of the top court, spoke after a graduation ceremony at Shue Yan University in North Point yesterday where he received an honorary doctorate in law.

Bokhary said he was "100 per cent in support of the idea of democratic development", and he praised the student activists joining the Occupy movement, who he said were pursuing their own cause and "the future of Hong Kong".

But he said society comprised different interests, including those of the police and of citizens complaining about the inconvenience caused by the movement, which couldn't be ignored.

In a speech after receiving the degree, Bokhary lamented the high cost of living in the city, especially skyrocketing property prices. "There was a time in Hong Kong when a good education more or less guaranteed commensurate employment or professional advancement," he said. "That is no longer so." He said "we will see" if the Occupy movement could make a difference.

Separately, Monetary Authority chief Norman Chan Tak-lam told 610 degree recipients at Chinese University yesterday that "not everything can be achieved in one go" and "sometimes taking a step back is necessary".

He reminded students that they should not give up on what they strove for, even though results might take generations.

Scores of students opened umbrellas in a symbol of protest when the national anthem played. Vice chancellor Professor Joseph Sung Jao-yiu said they did not cause disruption or show disrespect. Baptist University president Professor Albert Chan Sun-chi had condemned similar protests earlier this week.

This article appeared in the South China Morning Post print edition as Rule of law will survive, judge says

'One country, two internets', and why we need to protect it

PUBLISHED : Friday, 21 November, 2014, 10:43am

Late on Tuesday, a small group of people charged the Legislative Council building and broke a glass panel. Reports indicate they did so because they feared the passing of “Internet Article 23”. The original Article 23 is of course the controversial national security bill that provoked half a million Hong Kong people to protest in the streets in 2003. So what exactly is “Internet Article 23”, and should we be concerned?

“Internet Article 23” is actually more than one bill. Lawmakers and advocacy groups use it to refer to at least two different regulations, both with the potential to seriously undermine the free and open internet we enjoy in Hong Kong.

One is the Copyright Amendment bill, a much needed update to the otherwise outdated copyright bill. But many fear that it will punish citizens for remixing original content with social or political commentary as parody or satire. To understand why people are concerned, you only need to take one quick look online or walk by the Occupy areas: among the many art pieces, one of the most popular is a life-size cutout of president Xi Jinping holding a yellow umbrella that many people take selfies with.

The other regulation in question is the Computer Crimes Ordinance. Originally intended to battle computer fraud and hacking, it has been drafted in such a way that it has serious potential for abuse. The most recent case involves the arrest of a citizen for “inciting” others to commit an offence. His crime? Posting a message on an online forum asking others to join him in the pro-democracy protests; the original post has been removed and the police have so far declined to comment on the specifics of the case.

Let’s not forget what is at stake. We only need to look across the border to see a tightly monitored, closely controlled internet where citizens have to watch what they say to each other, even on seemingly private messenger apps such as WeChat. Then they might find themselves at a dead end if they try to find out what is going on; Sina Weibo and Baidu have been filtering search results for “Hong Kong students”, “Hong Kong tear gas” and “true universal suffrage”. And because people started sharing yellow umbrella pictures, Instagram is now the latest member to the club of global internet platforms that are blocked in China, joining Facebook, Twitter and YouTube, amongst others.

In contrast, we have a free and open internet in Hong Kong. Anyone can share their story and decide for themselves what is meaningful or not; no longer does a small and powerful elite determine this for the rest of society. Let’s be clear: a free and open internet doesn’t mean that people can say whatever they want without any consequences; all countries regulate speech to some extent. But it does mean that the conversation is open and inclusive: whether you are a yellow, blue or red ribbon supporter, you don’t have to ask anyone for permission to speak.

Whether you agree with the protesters or not, it is undeniable that they have breathed new life into a conversation that most people had given up on, a conversation about the future of Hong Kong and the status of “one country, two systems”. Sometimes we disagree or even yell at each other, but that’s what it means to have a honest, frank and real conversation, warts and all.

To my knowledge, the Hong Kong government hasn’t censored anything related to the protests. This is surely a good thing. But if the last few weeks have taught us anything, it is that our "one country, two systems" setup isn't sacrosanct or set in stone. That is why I am asking all of us to keep a close eye on “one country, two internets” and to make sure we preserve and protect the free and open internet in Hong Kong.

The author is an assistant professor at the School of Journalism and Communication at the Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Real radicals in constitutional debate are those who want to cast aside Hong Kong's core values

Stephen Vines says, by contrast, protesters seek to preserve the city's uniqueness

PUBLISHED : Friday, 21 November, 2014, 1:56pm

Protesters want to preserve the characteristics that make this place unique in China; rule of law and freedom is an essential part of this agenda. Photo: AFP

In all the noise and anger that surrounds the umbrella movement, one vital point appears to have been overlooked.

This is that the fundamental aim of most protesters is a conservative one, namely to preserve the unique character of Hong Kong.

Having spent a great deal of time talking to the protesters, especially the students, I keep hearing the same refrain: "We don't want Hong Kong to become just another Chinese city."

They want to preserve the characteristics that make this place unique in China; rule of law and freedom is an essential part of this agenda.

Of course, they also want to see a democratically elected government and there is no suggestion here that this is a side issue. But drill down to what fundamentally motivates these protests and you keep coming to this core issue of preservation.

The real radicals in Hong Kong want to see it becoming a very different sort of place where the central government makes all the big decisions and where core values that distinguish the Hong Kong system from that of the mainland are cast aside.

They shout very loudly about the need for adherence to the "one country, two systems" principle but, in practice, focus only on the "one country" part of this equation.

This was vividly illustrated when the radicals clamoured to support Beijing's ruling on the future of constitutional reform, even though the Basic Law prominently asserts the "high degree of autonomy" vested in the government of Hong Kong.

As power has eked away from the Hong Kong government and it is clear that major decisions affecting the SAR are not going to be taken at the local level, the protesters are struggling to secure adherence to the Basic Law and to protect what the law describes as safeguarding "the rights and freedoms of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region".

It is quite extraordinary how the portrayal of the two main parties to the constitutional debate has been turned on its head, with those focusing on preservation being labelled as radicals and those advocating fundamental change being labelled as conservative.

It may be argued that the labels really do not matter. There is something in this, but history shows that it is easier to preserve the status quo than to change it.

Therefore, in many ways, the umbrella movement should find it easier to achieve its fundamental conservative goals than did the 1989 Tiananmen Square protesters, who sought a fundamental change in a system they were certainly not angling to preserve.

Hong Kong's situation is admittedly unusual because the norm is for the younger generation to press for radical change while the older generations seek preservation of the status quo.

But, of course, Hong Kong's younger generation is not devoid of a desire for change; this is most certainly the case when it comes to democratic reform.

The result is a strange hybrid of desire for change matched by a yearning to preserve the status quo. This is not a typical state of affairs but reflects the many hybrid aspects of Hong Kong life.

This is why this place is seen as a bridge between the East and West, why full-throttle free enterprise is accompanied by a great deal of state intervention and why Hong Kong's most famous drink, nai cha, Hong Kong-style milk tea, is a culture-bridging drink.

Encompassing change and preserving the best of what we have is no easy task. However, the umbrella movement has already secured its place in history by ensuring that those who want to demolish Hong Kong's freedoms and liberty can expect formidable resistance as they do their worst.

The harder part of the movement's job is to secure democratic reform.

Stephen Vines is a Hong Kong-based journalist and entrepreneur

This article appeared in the South China Morning Post print edition as The real radicals want core Hong Kong values cast aside

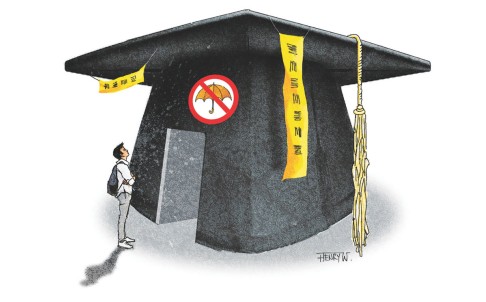

Where should universities draw the line on rights and freedoms?

Surya Deva says the umbrella movement raises important questions about human rights and freedoms on HK campuses, and is a reminder that restrictions should not be imposed lightly

PUBLISHED : Friday, 21 November, 2014, 3:41pm

Universities are where students, teachers and others should be able to discuss, debate and disagree on any issue without fear.

The ongoing umbrella movement has triggered a volcano of creative imagination in Hong Kong, with new ideas, governance paradigms and legal principles being tested almost every day.

Baptist University president Albert Chan Sun-chi recently refused to present degree certificates to graduates carrying yellow umbrellas on to the stage as they showed disrespect for the solemnity of the occasion. To reciprocate, a few graduates declined to accept certificates from him.

It has also been reported that students at City University have been told verbally not to hang a "Democracy: Now or Never" banner at the entrance of the university library. Otherwise, they risk disciplinary action. Then there was the controversy surrounding alleged civil rights abuses during the visit of Li Keqiang , then a Chinese vice-premier, to the University of Hong Kong campus in August 2011.

All these scenarios raise important questions about human rights within the campuses of Hong Kong's publicly-funded universities and the limits universities can place on the exercise of such rights.

It goes without saying that the Hong Kong government has an obligation to respect, protect and fulfil human rights under the Basic Law and the Bill of Rights Ordinance. These three-fold duties apply equally to public universities. So, the duty is not merely negative in nature: universities are expected to take a number of positive steps to ensure the human rights of all their stakeholders are adequately safeguarded on campus.

Of all the human rights, the one that stands out in the context of educational institutions is freedom of speech and expression. Universities are where students, teachers and others should be able to discuss, debate and disagree on any issue without fear. Innovation and creativity mushroom in a process of open engagement, rather than when debates take place within set contours.

Graduation ceremonies are an important facet of students' life at university. And while they are solemn occasions, they are also full of symbolism, reflected, for example, in the academic dress worn by graduates. If universities mandate graduating students to carry these symbols on to the stage, why not a small yellow umbrella as a symbol of the pursuit of the constitutional goal of universal suffrage?

If yellow umbrellas are not allowed on the convocation stage, would it be acceptable for students to take umbrellas into class or would it lead to their expulsion from the room? And how should one deal with faculty members who might find it offensive for students to wear yellow ribbons, or a cross for that matter, while in laboratories?

Where to draw these lines and how? There are at least two difficulties. First, it seems universities, like many corporations, are not fully aware of their human rights responsibilities. Universities might think that, as long as they accomplish their primary goal of nurturing learning and research, and in turn climb the ladder of world rankings, they are fulfilling their mission. But such a narrow compass is neither legally sound nor socially beneficial. Rather than using human rights or sustainability as part of a public relations exercise, universities should weave human rights into everything they do.

Second, each and every action of universities - from the hiring and firing of staff, to regulating the behaviour of students and the accessibility of campus to people with different needs or views - should be tested on the touchstone of human rights. They should be asking whether disallowing a yellow umbrella as a symbol on the convocation stage or denying students a prominent place to display banners would be consistent with the Basic Law and Bill of Rights Ordinance.

It should not be too difficult for universities to realise that freedom of speech and expression should be restricted - and then, too, in a proportional manner - only on certain grounds such as respect for the rights or reputations of others, or the protection of national security, public order, public health or morals. Moreover, such restrictions could only be imposed according to validly enacted regulations.

To avoid a repeat of the scenario that led to James Tien Pei-chun's expulsion from the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference for saying that Leung Chun-ying should quit as chief executive, it would also be desirable for newly appointed university presidents to resign from political positions. It is not irrelevant that Professor Chan's membership of the CPPCC fuelled certain perceptions about his actions.

Universities and other public authorities should also ask themselves another question: Why are the protests taking place in unusual locations or in an unusual manner - whether by occupying the streets for close to two months, by hanging a banner on the Lion Rock or now by unfurling yellow umbrellas on the convocation stage?

One reason is the lack of conventional spaces for engagement with decision-makers to raise legitimate concerns. Plus, there is little in the way of formal institutions, either in Hong Kong or Beijing, where democracy activists can engage the local or central government in constructive dialogue. This has forced people to find innovative and unprecedented ways to protest.

Human rights are hardly absolute, inside or outside university campuses. Universities can impose reasonable restrictions but they should not result in making human rights illusory. Nor should public educational institutions be operated as private shops with not enough space for human rights on their shelves.

Surya Deva, an associate professor at City University's School of Law, specialises in business and human rights, and comparative constitutional law. The views expressed here are the author's own

This article appeared in the South China Morning Post print edition as Degree of rights

Split within Occupy deepens as splinter group challenges leadership

PUBLISHED : Friday, 21 November, 2014, 5:29pm

The split among pro-democracy protesters deepened last night with radicals confronting the campaign leadership to demand an equal say on the movement.

The drama began as dozens of protesters who answered an internet appeal to confront the leadership marched, some wearing masks, to the main stage of the Admiralty rally site at 8pm.

They carried placards reading "you do not represent us" and shouted at speakers on the stage.

"We have not been allowed to express our views freely on stage," Samuel Chuang, one of the challengers, said. "If we say something the emcees do not like, they then add their comments later to 'correct' our speech."

Protesters who had been camping at the site described the radicals as "troublemakers" and said they would film any who caused trouble so they could be held accountable later.

Chuang also said the marshal system set up to keep order at the protests was unnecessary. No one, he said, should have the right to overrule others in a social movement, especially when those keeping order were not elected by the people.

He admitted he was present when clashes broke out early on Wednesday when a group of masked men tried to storm the Legislative Council building, but said he did not want to see any violence.

Other radicals, though, said marshal team leader Alex Kwok Siu-kit should not have acted to block Wednesday's action.

Oscar Lai Man-lok of student group Scholarism - one of the key organisers - said the main stage was always open to different voices. He said the marshal system was in place in case of incidents such as one when Apple Daily publisher Jimmy Lai Chee-ying had offal thrown over him.

Wong Yeung-tat, leader of radical group Civic Passion - several members of which are alleged to have been involved in Wednesday's disturbances - called on protesters not to storm the stage. "Pan-democrats have formed a united front with the police and labelled the strugglers as thugs," he said. "I call on everyone to be restrained, to remain calm and rational and not to fall into the trap. [We] should not offer pan-democrats an excuse to retreat, as they have planned."

Lai said the organisers would be happy to hold a public debate on the marshalling system with the group.

Meanwhile, a report by British television station Channel 4 has quoted a senior member of a Hong Kong triad gang as saying that Occupy protesters were infiltrated by troublemakers. The man - called "Mr Kong" - said triads were paid by the Communist Party to disrupt and discredit the movement.

This article appeared in the South China Morning Post print edition as Split deepens among Occupy protesters

沒有留言:

張貼留言