Occupy Central

Occupy Central is a civil disobedience movement which began in Hong Kong on September 28, 2014. It calls on thousands of protesters to block roads and paralyse Hong Kong's financial district if the Beijing and Hong Kong governments do not agree to implement universal suffrage for the chief executive election in 2017 and the Legislative Council elections in 2020 according to "international standards." The movement was initiated by Benny Tai Yiu-ting (戴耀廷), an associate professor of law at the University of Hong Kong, in January 2013.

Umbrella Movement

The Umbrella Movement (Chinese: 雨傘運動; pinyin: yǔsǎn yùndòng[1]) is a loose political movement that was created spontaneously during the Hong Kong protests of 2014.[2] Its name derives from the recognition of the umbrella as a symbol of defiance and resistance against the Hong Kong government, and the united grass-roots objection to the decision of the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress (NPCSC) of 31 August.

The movement consists of individuals numbering in the tens of thousands who participated in the protests that began on 28 September 2014, although Scholarism, the Hong Kong Federation of Students, Occupy Central with Love and Peace, groups are principally driving the demands for the rescission of the NPCSC decision.

The movement consists of individuals numbering in the tens of thousands who participated in the protests that began on 28 September 2014, although Scholarism, the Hong Kong Federation of Students, Occupy Central with Love and Peace, groups are principally driving the demands for the rescission of the NPCSC decision.

OCCUPY CENTRAL - DAY 72: Full coverage of the day’s events

Visa row a case of failed diplomacy, from London to Hong Kong

Mike Rowse says the brouhaha over British MPs' visit could have been averted

PUBLISHED : Monday, 08 December, 2014, 6:23am

Did a whole group of British MPs really have to visit in such a high-profile way while Occupy Central is in progress? Photo: AFP

I don't know about you, but I have been completely baffled over the recent row between Beijing and London concerning a proposed visit to our city by some members of the British Parliament.

Things got off to a bad start with the reference to visas in a Post story last week, "Cameron steps into row over lawmakers' visas". A spokeswoman for the Foreign Ministry in Beijing was quoted as saying: "Whether to grant visas, and who to give them to, are the decisions of the country."

There are two things wrong with this statement: first, British passport holders do not need a visa to enter Hong Kong; secondly, under the Basic Law, control over entry to the special administrative region is one of the matters specifically reserved for the Hong Kong government under "one country, two systems".

So the immediate reaction might be to query why someone who apparently has no authority over the subject - and clearly no knowledge about it either - is speaking to the media at all.

But the initial response may be too superficial. The British government and Parliament do have a legitimate interest in Hong Kong affairs, bearing in mind that the UK was a signatory with China to the 1984 Sino-British Joint Declaration, registered with the UN as an international treaty. So MPs can reasonably argue that they want to check how the treaty is being implemented.

But did a whole group really have to visit in such a high-profile way while Occupy Central is in progress? With emotions in the street running so high and tension over imminent clearance operations so severe, was this really the best time? Could they not have taken evidence from witnesses here by video conference, as when the last governor, Chris Patten, responded recently to an inquiry by the US Congress?

And if a site visit was deemed essential, could it not have been done in a low-profile way, with a handful simply slipping into the territory? Seen from this perspective, perhaps the Foreign Ministry spokeswoman was not so far out of line after all.

By deciding to come to Hong Kong in their collective official capacity as the House of Commons Foreign Affairs Committee, did the British MPs not tip the visit over the edge into the realm of foreign policy, thereby giving Beijing a legitimate locus? How would the British government have responded if the National People's Congress had sent a delegation to the UK to take evidence under oath about how Chinese people were being treated there?

But we are straying too far from the main point. There is far too much aggravation in the air. London is being too clumsy, Beijing oversensitive. Situation normal, the cynics might say.

But was there not a much better way for Hong Kong to have handled the whole brouhaha? Chief Executive Leung Chun-ying could have issued a statement along the following lines. "Hong Kong and the United Kingdom continue to enjoy a close and friendly relationship at all levels. We very much appreciate the interest our British friends have in our well-being. We understand why Members of Parliament like to keep abreast of events here. However, we are going through a brief period of turmoil and emotions are running high. We would not wish to inflame those sentiments further.

"We would therefore be grateful if the committee would not visit Hong Kong in its official capacity until things have calmed down. Later, when conditions have returned to normal, I would be happy to play host to Mr Richard Ottaway and his colleagues, visiting us in their private capacities."

Does that sound too diplomatic? Isn't the whole point of diplomacy to minimise friction and maximise points of common interest?

Mike Rowse is managing director of Stanton Chase International and an adjunct professor at the Chinese University of Hong Kong.mike@rowse.com.hk

This article appeared in the South China Morning Post print edition as A case of failed diplomacy, from London to Hong Kong

British MPs barred from Hong Kong to stop ‘oil being poured on fire’: Chinese ambassador

British MPs were banned from entering Hong Kong because their visit could give Occupy Central activists 'the illusion of external support', the Chinese ambassador to Britain has said.

Scholarism plans escape route for Occupy's weakest members as 100 join ‘relay hunger strike’

Scholarism convenor Joshua Wong Chi-fung said the student group would arrange for school pupils and the edlerly to leave Occupy's main protest site in Admiralty if police started clearing up.

PUBLISHED : Monday, 08 December, 2014, 2:34pm

UPDATED : Monday, 08 December, 2014, 2:34pm

Officials' dire warnings about Occupy protests aren't borne out by the realities

Peter Kammerer says the overblown warning about Occupy's damage to our economy and image only hurts the government's credibility

Occupied streets and protesting students are all to do with my job, but nothing to do with my everyday life. My home, office and places that need to be visited have all been far removed from the trouble spots. Yet there I was recently on holiday in Australia, with Hong Kong seemingly of the utmost interest to all who learned where I live. Through their media connectivity, I was kept informed up to the minute of what was taking place, despite my efforts to switch off.

"Those students who are protesting have a lot of guts," the woman who helped me to the city shuttle bus opined shortly after I arrived at Brisbane airport. The receptionist at the hotel I was checking into looked up from the registration form I had just filled out and said: "That was a terrible murder in Wan Chai, wasn't it?" There were similar comments throughout my two-week stay; the awareness of ordinary people about events in a city that I would have thought of little or no interest to them was astonishing. Since returning, I've heard similar accounts from work colleagues and friends who have been on trips to other countries, the theme being that the world isn't as small, insular and uninformed as some officials make it out to be.

Financial Secretary John Tsang Chun-wah has been on the frontlines of the anti-Occupy bandwagon, warning that the demonstrations will have dire consequences for Hong Kong's economy. Just over 10 weeks since they began, there is no sign of such an impact; there has been an economic slowdown, but that is Asia-wide and cannot be specifically put down to the protests. Contrary to his previous predictions, the Hang Seng index has been largely unaffected, while tourism numbers, retail sales and property transactions are up. Some shops near protest zones have undoubtedly suffered, as have the bus, tram and taxi companies - but there are also some among such firms which have benefited through being innovative.

The internet means that reality is just a click or two away. Hong Kong's success is based on open borders, a free market and high-quality infrastructure. Most of us carry smartphones and those wanting specific information have no difficulty finding it, especially when the story is hot. For officials to tell a different version of events to those that others see and hear is to harm their credibility and damage faith in the city they are governing.

I am no supporter of the way the students have gone about their campaign. People should be able to govern themselves, but attaining that aim has to first be done through lobbying, negotiations and finding a common path. If these fail to bear fruit after years, perhaps decades, then there is reason to resort to more forceful measures. Breaking the law by blocking roads, stopping the government from doing its business, barring customers from shops and taking up makeshift weapons are harmful, not beneficial, to their cause.

But law-breakers or not, it is wrong to contend that the protesters are damaging Hong Kong's business environment and image. The packed aircraft flying from Brisbane anecdotally told me that. The support voiced for the "plucky protesters" and the financial data confirmed it.

Peter Kammerer is a senior writer at the Post

This article appeared in the South China Morning Post print edition as Reality intrudes

Are hunger strikes effective? What Occupy students could learn from historical protests

As Hong Kong student leader Joshua Wong calls off his fast after four days, we look at some historical hunger strikers

On Saturday, Hong Kong student activist Joshua Wong Chi-fung, of the group Scholarism, ended a hunger strike he had initiated in an attempt to force a dialogue with the government. His fast lasted 108 hours.

Hunger strikes have been used by a wide variety of political dissidents in a number of countries, with mixed success. While Gandhi was something of a master at holding his own body hostage to extract concessions from his opponents, other hunger strikers often had to pay a high price for victory, if it came at all.

Mohandas Gandhi

During the fight for Indian independence, Mohandas “Mahatma” Gandhi often used fasting as a form of non-violent resistance. Between 1913 and 1948, he went on hunger strike a staggering 17 times, with the longest fast lasting 21 days.

Due to his stature and popularity, Gandhi’s fasts were successful both in attracting international media attention and forcing action from those he sought to pressure.

In 1932, he went on hunger strike to protest a British proposal to separate India’s electoral system by caste, giving the so-called “untouchables” their own separate political representation for a period of 70 years.

“This is a god-given opportunity that has come to me to offer my life as final sacrifice to the downtrodden,” Gandhi said, vowing to “fast until death” unless the plan, which he felt would permanently divide India’s social classes, was dropped.

After a six-day fast, a settlement was reached and the separation decision was reversed.

As his influence and notoriety grew, Gandhi increasingly turned to fasting as a way to settle disputes, even after independence. Due to his popularity with Indians of all religions, hunger strikes often proved effective in stopping the inter-communal violence which surrounded India and Pakistan’s eventual split and independence.

Gandhi fasted three times between 1943 and 1948 to call for unity between Muslims and Hindus in Delhi, including one hunger strike which lasted 21 days.

Gandhi started his last fast on January 12, 1948, again against inter-communal riots in the Indian capital. After six days without food, faith and political leaders agreed to meet and discuss peace in the city. But soon after ending his fast, Gandhi was shot and killed by a Hindu extremist.

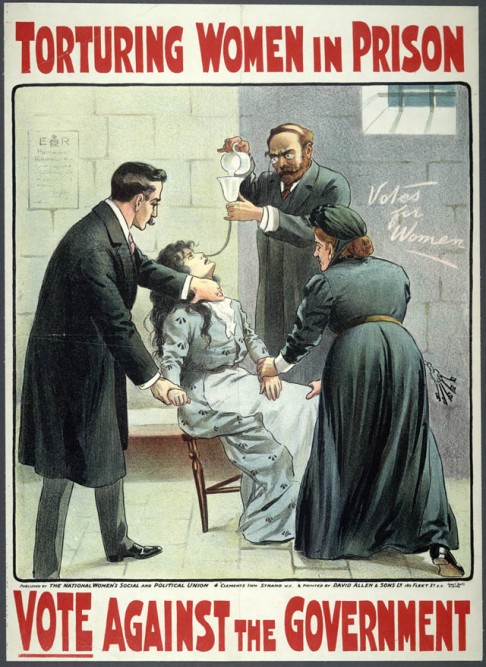

Emmeline Pankhurst

One of the leaders of the British suffragette movement who helped women win the right to vote, Emmeline Pankhurst and her comrades often used hunger strikes as a form of protest against the British establishment, particularly during periods of imprisonment.

After the hunger strike was approved by Pankhurst’s Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) as a form of resistance, Marion Wallace Dunlop, imprisoned for writing an excerpt from the Bill of Rights on a wall in parliament, began fasting to protest conditions in prison.

When this proved effective, other imprisoned members of the WSPU took up the tactic.

Suffragette hunger strikers were often subjected to horrific force-feedings, during which steel gags were used to hold the mouth open and a plastic tube was inserted down their gullet. The tactic caused a split between Pankhurst’s group and more moderate suffrage organisations, who denounced fasting as mere publicity stunts.

Pankhurst was arrested in 1912 and imprisoned in Holloway Prison, where she personally staged her first hunger strike and was force-fed.

“Holloway became a place of horror and torment. Sickening scenes of violence took place almost every hour of the day, as the doctors went from cell to cell performing their hideous office,” she wrote in her autobiography.

After parliament passed the so-called “Cat and Mouse Act”, suffragettes undertaking hunger strikes were released from prison as soon as they became ill, and re-imprisoned after their health improved. Though it was intended to reduce the public relations fallout from force-feeding fasting prisoners, the illiberality of the act led to widespread outrage and loss of support for the Liberal government.

The Representation of the People Act, passed in 1918, was the first British law to give women a limited right to vote. They would not achieve the same franchise as men until 1928.

Bobby Sands

A member of the militant Provisional Irish Republican Army, Bobby Sands was the leader of a 1981 hunger strike by Irish republican prisoners in Northern Ireland, during which 10 participants starved to death in succession.

Protests broke out in prisons across Northern Ireland in 1976 when the British government removed Special Category Status for convicted paramilitary prisoners. Prior to this, republican prisoners had been classed as something akin to prisoners of war, granting them special privileges compared with regular criminals.

Violence broke out between prisoners and guards, and in 1978 a “dirty protest” was launched, in which prisoners refused to wash and covered the walls of their cells with excrement. This escalated in 1980 to a hunger strike in which seven prisoners took part, demanding the restoration of many of the rights granted by Special Category Status.

That strike ended after 53 days when the British government released a settlement proposal which appeared to concede to prisoners’ demands. However, no further action was taken and on March 1, 1981, prisoners resumed the strike when Bobby Sands refused food.

WATCH: Trailer for Hunger, award-winning film directed by Steve McQueen and starring Michael Fassbender about hunger striker Bobby Sands

Five days into the strike, Sands was elected to the House of Commons through a by-election, leading many to hope that a settlement could be negotiated, as he was now a Member of Parliament.

British prime minister Margaret Thatcher refused to reconsider the removal of Special Category Status for paramilitary prisoners, saying: “Crime is crime is crime, it is not political.”

The government’s resolve did not waver even as Sands approached death. “If Mr Sands persisted in his wish to commit suicide, this was his choice. The government would not force medical treatment on him,” Northern Ireland minister Humphrey Atkins said.

Sands died on May 5, 1981, after 66 days of fasting. In the weeks following his death, three more striking prisoners died, prompting criticism from the Republic of Ireland government over the British government’s handling of the protests. In all, 10 hunger strikers died before the strike was called off on October 3.

Three days later, the new Northern Ireland minister James Prior announced partial concessions.

Though widely seen as a victory for the Thatcher government at the time, the hunger strikes marked the emergence of Sinn Fein as an electoral force in Northern Ireland.

Guantanamo Bay prisoners

Since 2005, many prisoners at the US military base in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, have carried out hunger strikes in protest at their detention without trial. Information about prisoners is not widely available and it is unclear how many have taken part or are taking part in fasts and for how long.

In mid-2005, at least 50 detainees went on hunger strike to protest their imprisonment and conditions. During this time, human rights agencies say that fasting prisoners were force-fed via a tube inserted through their nose into their stomach.

The initial strike ended after 26 days when prison authorities agreed to bring standards at the camp into compliance with the Geneva Conventions in July 2005.

However, by September, The New York Times reported that as many as 200 prisoners, or one-third of the camp, were again on hunger strike, with as many as 20 being force-fed.

“We will not let them starve themselves to the point of causing harm to themselves,” camp spokesman Major Jeffrey Weir told the paper.

In December 2005, the military reported that there were 84 hunger strikers taking part in the protest. By April 2008, after a large number of prisoners were repatriated or transferred to other jurisdictions, The New Yorker reported that there were only 10 prisoners still on hunger strike.

WATCH: Yasiin Bey (Mos Def) undergoes force feeding to protest the use of the tactic on Guantanamo Bay prisoners

A new wave of hunger strikes began last year. By July, 106 of 166 detainees were participating, with 45 of them being force-fed, according to prisoners’ lawyers. The military disputed this number, saying only 21 men were taking part in the strike.

Following widespread media attention, including a video in which actor and musician Yasiin Bey (aka Mos Def) underwent force-feeding, the US military announced in December last year that it would no longer release information about hunger strikes. The last figures released showed there were 15 strikers, all of whom were being tube-fed.

Rear Admiral Kyle Cozad, who oversees Guantanamo, admitted to Agence-France Presse last month that force-feeding was still occurring. He defended the practice on the grounds of medical necessity.

“I have no moral or ethical issue with it,” Cozad said.

Follow @jgriffiths on Twitter

World must hold Beijing accountable for its actions in Hong Kong

Stephen Young says foreigners are right to show support for local people

Police officers clearing the barricades in the Mong Kok occupied area last month. Photo: AP

As the world's attention has turned to what some call the "umbrella revolution" in Hong Kong, it is worth looking at the historical context.

Thirty years ago, when Deng Xiaoping was negotiating with Margaret Thatcher over the return of Hong Kong to Chinese sovereignty, the territory was seen as a prized asset. Not only would a deal add this thriving commercial city to China's territory as it was digging itself out of decades of turmoil under Mao Zedong , but it would also signal the end of a long period of colonialism and unequal treaties.

Deng's pledge to retain the essential character of the territory for at least 50 years was critical both to Britain's interests, and even more so to those of the people of Hong Kong itself.

Much has changed since then. China's dramatic emergence on the global economic scene somewhat diminishes the role of Hong Kong today, though it remains a thriving business and financial hub with unparalleled international links.

Yet Beijing's leaders seem increasingly concerned about the negative spillover effect on China's restless masses of a city where individual freedoms hold sway in a way that they do not across the border. With tens of millions of mainland Chinese tourists visiting the city each year, Beijing now has to worry that they may be bringing home with them dangerous new ideas.

It is in this context that President Xi Jinping decided to deny the aspirations of those in Hong Kong advocating genuine universal suffrage in the selection of the next chief executive in 2017.

As someone who grew very fond of the people of Hong Kong during my recent tenure as US consul general there, it saddens me to see their aspirations thwarted by a tone-deaf leadership to the north. But I am not surprised.

The Communist Party continues to delude itself that more than three decades of economic advancement need not be accompanied by any real expansion of political freedom. In so doing, it ignores the trend towards greater political openness followed by so many of its Asian neighbours, like South Korea, Taiwan, the Philippines and Indonesia.

Beijing has also recently turned up its objection to criticism of its treatment of Hong Kong by the international community, particularly targeting Britain and the US. It claims that this is interference in China's internal affairs.

Yet, 30 years ago, China and the UK formally lodged their joint agreement on Hong Kong's return in the United Nations, precisely because they wanted global support for their agreement and its promises.

Therefore, it is perfectly natural today for the international community to demonstrate its support for Hong Kong's continued special status.

There is much to admire about Hong Kong and its unique status as a special administrative region of China. The rule of law, free press, tradition of peaceful protest, and many other freedoms, have all become enduring characteristics of this special city, though events of the past several days are threatening to diminish their sparkle.

For now, however, Beijing's conservative leadership seems determined to set definite new limits on the promise of "one country, two systems" as it applies to Hong Kong. This sends a very negative signal to the millions of Hongkongers who took China at its word in the run-up to the 1997 turnover.

It sends a cautionary note to the 23 million citizens of Taiwan, who have also been considering closer ties to mainland China, but are understandably sceptical that Beijing leaders' promises can be trusted. It is also a blow to the many people in China who had hoped economic success would be followed by a greater voice for them.

The world must make it very clear to Beijing's leaders that we are watching what they are doing to Hong Kong today.

We must hold them accountable for their actions to undermine Hong Kong's desire for a representative government whose leaders they can choose themselves.

Ambassador Stephen M. Young (retired) was US consul general to Hong Kong from 2010 to 2013. These views are his own and do not represent those of the US government

This article appeared in the South China Morning Post print edition as World must hold Beijing to account for its actions in HK

Legco may seek injunction to clear Occupy protesters from complex: Jasper Tsang

The Legislative Council may seek a court injunction to clear the protesters occupying parts of the Legco complex, Legco President Jasper Tsang Yok-sing said on Monday.

The final push: police finalise plans to clear Hong Kong streets of Occupy protesters

Over 3,000 police officers could be deployed to clear the biggest Occupy camp in Admiralty and the protest zone in Causeway Bay on the same day this week, according to police sources.

沒有留言:

張貼留言